ASM Podcast: 2023 NSC Winners’ Journey – From Malacca to Kunming

November 14, 2024

Peluncuran Pelan Transformasi AIR 2040

November 14, 2024As part of the TropSc™ 2024 Pre-conference Webinar series, The Tropical Science Foundation organised a webinar titled Mangroves: Guardian of Our Coasts on 26 July 2024.

The webinar was moderated by Associate Professor Dr Aldrie Amir. Dr Ahmad Aldrie Amir is a Senior Lecturer and Research Fellow at the Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. He is also the Coordinator of the Malaysian Mangrove Research Alliance and Network (MyMangrove) and the Commission Member of the IUCN SSC Mangrove Specialist Group. He has an extensive experience in studying mangrove ecosystems in Malaysia, specialising in mangrove ecology, conservation, management and governance.

The webinar featured speakers who each presented on their field of expertise within the scope of magrove ecosystem management. First to present was Professor Dixon T. Gevaña, Director of the Forestry Development Centre at the University of the Philippines. Professor Dixon presented on shaping the future of mangrove governance in Southeast Asia.

Professor Dixon stated that the Southeast Asian region has lost 110,000 hectares of mangrove in the past two decades; the mentioned figure is almost one-fifth of Malaysia’s total mangrove area. He also mentioned that as of 2015, the region has about 4.5 million hectares left, with an annual deforestation rate of 0.34%, meaning that we are losing mangrove areas faster than we are replanting.

Professor Dixon highlighted the importance of conserving the mangrove ecosystem by stating the volume of carbon it is able to store. A mangrove forest is able to store 3 to 4 times as much carbon than its boreal, temperate, or tropical upland counterparts across three levels: above-ground, soils 0-30 cm depth (roots included) and soils below 30 cm depth. As such, deforestation of magroves would translate to volumious carbon emissions, which is detrimental to the planet. According to Professor Dixon, every year we lose about 21,000 hectares of mangrove forests globally, and it is most serious in the Southeast Asian region as around 50% of the world’s mangrove lies in this region.

Professor Dixon cited sediment loss from black sand mining as another outcome of mangrove deforestation; sediment loss eventually leads to coastal erosion. Conversion of mangrove land into oil palm plantations and its associated activities (e.g. road development) also hinders coastal sediment recharge; sediments from upstream are unable to flow to coastal regions, leading to eventual erosion and destruction of coastal mangrove forests. Professor Dixon also cited construction of seawall and coastal roads as sources of mangrove destruction. Mangove forest fires used to be virtually impossible as they will be underwater for a period of time daily due to tidal changes. However, improper solid waste disposal in mangrove areas await the perfect time to catch fire, hence burning down these precious mangrove areas. In addition, upstream cattle ranching also introduces sedimentation in downstream mangrove areas, clogging up the roots and suffocating mangrove trees.

To address the issue of mangrove destruction, identifying and understanding the drivers, pressures, states, impacts and responses to this issue is important. Understanding the current situation leads to knowing the impact of this issue; identifying the drivers and pressures will help pinpoint the right sectors that can drive positive change. In turn, the most effective responses can be implemented to ensure the preservation and rehabilitation of mangrove forests.

Based on sea level rise projections, 26% of mangrove regions, particularly in the Southeast Asian region, will be submerged by the year 2100.

Professor Dixon then presented the futures triangle of SEA mangroves. The three corners of the triangle each corresponds to the actions, challenge, and opportunities/technologies of the past, present, and the future, in relation to the way forward of SEA mangroves.

Next, we had Associate Professor Dr Behara Satyanarayana from the Institute of Oceanography and Environment, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu. He presented on how mangroves contribute to a secured life and safe planet.

Dr Behara began his presentation with a poetic yet insightful introduction to the dynamic mangrove ecosystem. He also iterated that this ecosystem is prone to destruction either from natural causes or human interference.

Dr Behara stated that mangrove areas cover 14.5 million hectares, about 40% of which is situated in the tropical region. He mentioned the importance of mangrove areas as buffer regions to protect coastlines as well as the people living nearby.

Next, Dr Behara elaborated on the blue carbon science, which refers to organic carbon that is captured and stored by the oceans and coastal ecosystems (e.g. seagrass meadows, tidal marshes, and mangrove forests). Blue carbon ecosystems occupy the intertidal and shallow water environments where vertical accretion of soils is strongly influenced by sea levels.

The world’s mangrove forests, with their archetypal twisted roots protruding from the water surface, store more than 6 billion tonnes of carbon. Dr Behara highlighted that more than 6 percent of this amount is stored in Malaysia’s mangrove forests. He also mentioned that mangrove forests have a high carbon capture and burial rate and are able to store carbon on a millennial scale, i.e. a long period of time.

Dr Behara then talked about the significance of soil depth in effective and long-term carbon storage. 50 to 90% of carbon is stored below ground in mangrove forests. However, not many studies have been conducted that focuses on deep soil carbon and reported higher carbon stock; most studies tested mangrove soil carbon at depts of up to 1 metre only.

Dr Behara directed the audience to the Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve, one of the longest managed mangrove forests in the world. This mangrove forest is also a commercially managed mangrove forest where poles and charcoal are manufactured. At the reserve, Dr Behara and his team went to managed and unmanaged sites to extract 10-metre-deep sediment core samples. The research team found that a high carbon stock was discovered at the 3-4 metre depths. Additionally, carbon is still found even at the 10-metre depth albeit in smaller amounts. Dr Behara stated that this shows how important soil depth is for carbon storage. He also showed that unmanaged sites have a higher carbon storage, a natural and expected observation.

Next, Dr Behara showed the effects of losing mangrove ecosystems. Due to more than 50% of mangrove ecosystems at the risk of collapse, about 7,065 km2 more mangrove regions will be lost, and 23,672 km2 will be submerged by 2050. As a consequence, about 1.8 billion tonnes of carbon stored will be lost (estimated value at USD13 billion); 2.1 million lives will be exposed to coastal flooding; USD36 billion worth of properties will be lost; and a huge loss of fishing grounds as a source of food and income for coastal populations, among others.

The third panellist was Mr Muhammad Nurazmeel Mokhtar, Programme Officer (Field Operation) at Sabah Environment Trust, SET. He presented on the role of mangroves as guardians of our coasts.

Mr Nurazmeel started his presentation with an introduction to the Kota Kinabalu Wetland Ramsar Site, which sits in the heart of Kota Kinabalu (KK) city. He explained that the idea of lobbying for this area to be protected came when a group of environmentalists from WWF-Malaysia and other organisations “discovered” Likas Swamp or Likas Mangrove in the 1980s. However, at that time, the mangrove was populated by some-200 houses, which led to loss of mangrove habitats, waste disposal issues and low water quality caused by pollution.

Consequently, the area was declared a bird sanctuary in 1996 under the Sabah Land Ordinance (Cap.68), and further declared as a Cultural Heritage Site in 1999 under the States’s Cultural Heritage (Conservation) Enactment 1997. As a result, the area thrived and blossomed into a healthier mangrove ecosystem, as shown by Dr Nurazmeer via photos comparing the area’s conditions in 2003 and 2010.

Dr Nurazmeer highlighted the uniqueness of the KK Wetland Ramsar Site next: it is the smallest Ramsar Site in Malaysia (24 hectares, the last remaining mangrove forst along the coastline of KK city); it is the only NGO-managed Ramsar Site in Malaysia (by the Sabah Wetlands Conservation Society, or SWCS for short); and it is a model wetland centre in KK, where over 5,000 environmental education programmes have been organised for students, civil servants, and corporate sectors.

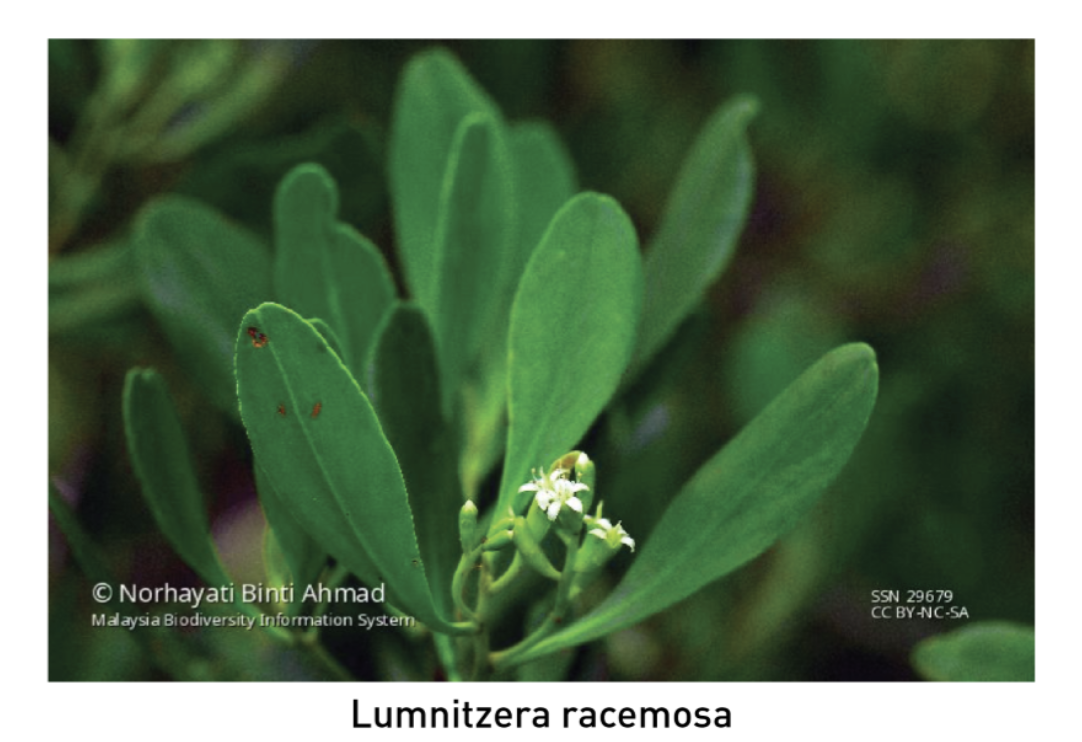

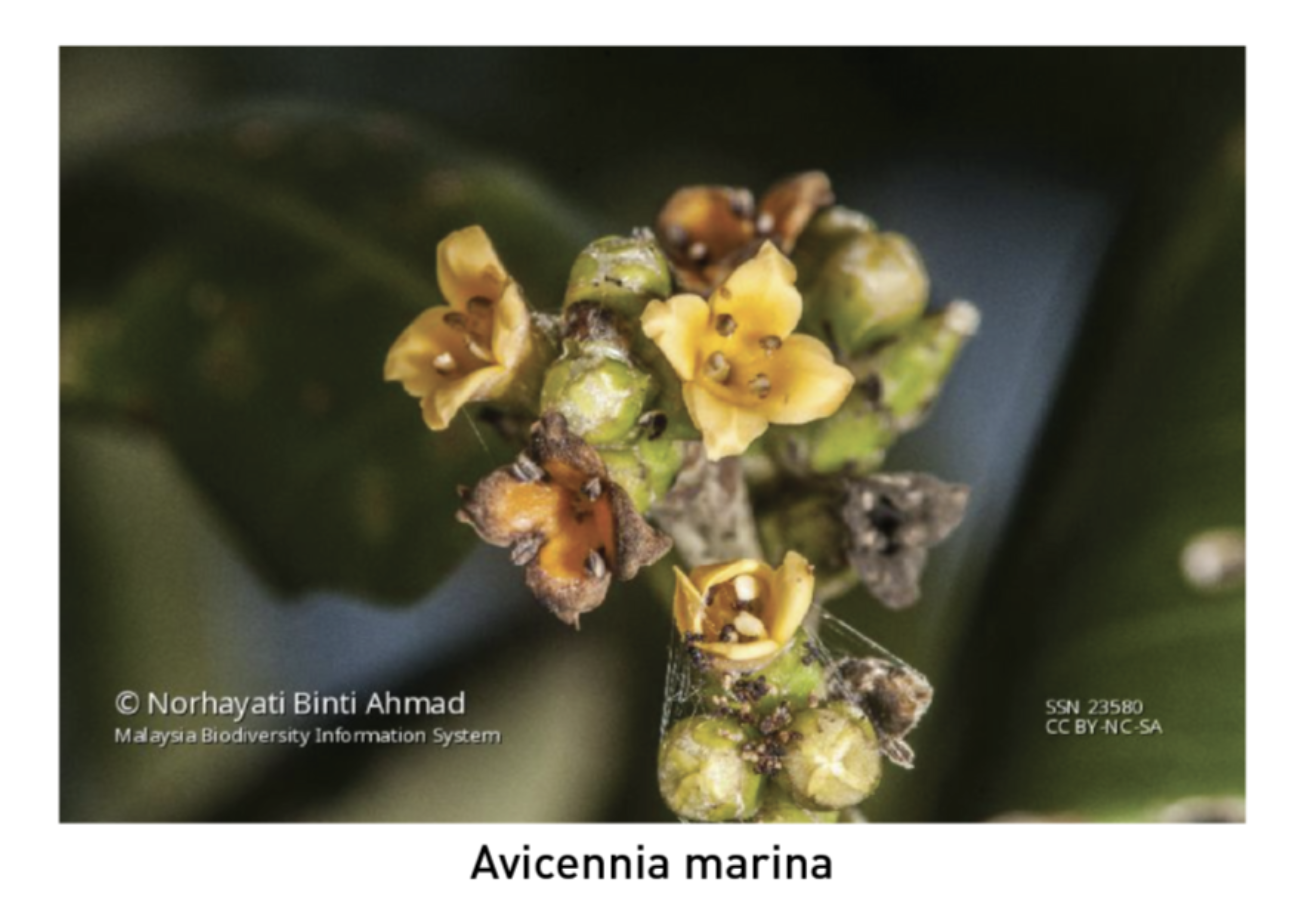

The SWCS has made an inventory of the flora and fauna in the KK Wetland Ramsar Site. Forty-one species of flora can be found within 24 hectares of mangrove forest, plus 203 species of fauna. Mr Nurazmeer explained that due to its small size, the KK Wetland Ramsar Site faces some issues, one of it being monoculture: the planting of the fast-growing mangrove tree Rhizophora mucronata in the early years without proper planning has led to it overpowering native species, such as Avicennia sp., Sonneratia sp., and Lumnitzera sp. (the latter has since become extinct in the KK Wetland Ramsar Site).

In essence, Professor Dixon and Associate Professor Dr Behara Satyanarayana highlighted severe threats to Southeast Asia's mangroves, which face high deforestation rates due to coastal development, agriculture, and mining. Mangroves, storing 3-4 times more carbon than other forests, are critical for carbon capture and coastal protection, yet 26% may be submerged by 2100. Dr Behara emphasised mangroves' unique ability to store carbon in deep soils and their vital ecosystem services. Mr Muhammad Nurazmeel Mokhtar rounded up the session by showcasing the success of the Kota Kinabalu Wetland Ramsar Site, a protected mangrove area fostering biodiversity.

As a result of this monoculture, the biodiversity of the Ramsar Site was also reduced; the population of Purple Heron (Ardea purpurea) and other migratory bird species has since dwindled caused by the lack of nesting spots due to the reduced tree species.

Next, Mr Nurazmeer explained how SWCS is trying to counter these issues. The SWCS carried out mangrove thinning from time to time as a two-pronged approach: to clear the view for tourism purposes (e.g. bird watching and building observation towers), as well as to open up areas that have high concentrations of wildlife and to promote the growth of mangrove associates (e.g. ferns and orchids), which would increase biodiversity in the mangroves.

Additionally, SWCS are also actively increasing species diversity on site by replanting displaced mangrove species such as Avicennia sp., and Sonneratia sp. Furthermore, SWCS is also adding mangrove species that would attract biodiversity, such as orchids and Lumnitzera littorea.

Mr Nurazmeer then mentioned an on-going initiative by the Sabah state to increase protected mangrove sites. They have proposed Klias Peninsula Wetland as the next Ramsar Site. The Klias Peninsula, which covers 130,310 hectares, is unique in that it contains both mangroves and peatlands and is situated between two districts: Beaufort and Kuala Penyu. He also mentioned a recent and upcoming Sabah Mangrove Action Plan announced by the Chief Minister of Sabah. Then, Mr Nurazmeer highlighted a funding opportunity offered by the Ramsar Regional Centre East Asia (RRC-EA) via its Wetland Fund. Proposals can be submitted to secure funding under two Thematic Areas: Thematic Area 1 (USD10,000) for wetland conservation and wise use to support the implementation of the 4th Ramsar Strategic Plan 2016-2024; and Thematic Area 2 (USD5,000) for the celebration of World Wetlands Day.

The International Day for the Conservation of the Mangrove Ecosystem raises awareness about the critical role of mangroves in coastal ecosystem, especially in tropical countries. Mangroves are biodiversity hotspot that provide habitat and breeding grounds for diverse marine and terrestrial species, thus supporting overall ecosystem health. They act as significant carbon sinks, mitigating climate change by sequestering large amount of carbon dioxide, a vital function for tropical nations facing severe climate impacts.

Mangroves also protect coastal communities by offering natural disaster risk reduction from erosion, storm surges, and tsunamis. Many tropical communities rely on mangroves for their livelihoods, including fishing, tourism, and sustainable forestry, making their conversation essential for local economies and food security. Additionally, mangroves contribute to water purification, sediment trapping, and nutrient cycling, which are crucial for sustaining agriculture, aquaculture, and environmental health.

Celebrating this day emphasises the importance of preserving and restoring mangrove forests to ensure they continue to provide this vital services, benefiting both nature and human communities for generations to come.